Project Status and Accomplishments

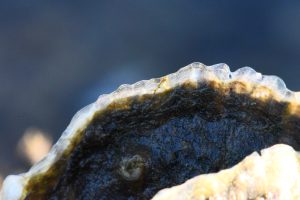

The Lone Cabbage Reef Oyster Restoration project was completed this summer marking the end of more than fourteen years of work in the region. This project, which was culminated by the successful restoration of a chain of oyster reef more than three miles long in 2018, is the largest successful oyster restoration project in Florida. Lone Cabbage Reef was historically a vibrant oyster reef at the mouth of the East Pass of the Suwannee River (see maps) providing fish and wildlife habitat, oyster harvests, and multiple ecosystem services including reducing wave action to help protect the shoreline. Over the last three decades, oyster populations on the reef declined, and eventually collapsed, and the once healthy oyster reef became a sand bar. Through field assessments and small experimental restoration efforts in 2010-2017 the project PIs identified a restoration approach that appeared to reverse the observed collapse and jumpstart the reef to recovery. With funding from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, a large restoration effort was planned and completed in the summer of 2018. This effort involved working with local contractors, quarry operators, and the men and women of the Cedar Key Oystermen’s Association to prepare the site and then place local dolomite limestone on the footprint of the degraded Lone Cabbage Reef. To mimic the complex shape of a natural oyster reef, multiple sizes of limestone rocks were used from six to thirty-six inches in size. Critically, the restored reef was built to a similar elevation as nearby healthy oyster reefs of about 15-18 inches. This project was led by UF faculty Bill Pine, Peter Frederick, and Leslie Sturmer.

Funded with support from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF), this project has been particularly noteworthy for its success in the Gulf of Mexico. “The Lone Cabbage Oyster Reef Restoration project represents a significant advancement in the re-establishment of a critical coastal resource,” said Jeff Trandahl, Executive Director and CEO of NFWF. “NFWF is pleased to have partnered with the state of Florida, the University of Florida, and local oyster interests to accomplish the large-scale restoration of historic oyster reefs in the Suwanee Sound, and looks forward to the lessons learned through this effort informing other large-scale oyster restoration practices across the Gulf.”

After the restoration in 2018, oyster populations were monitored each winter and salinity was measured every hour near the reef until February 2023. A key result is that this oyster reef restoration resulted in a rapid reversal of observed declines in oyster populations at the restored reef. Oyster larvae (called spat) were first found within a few months of completing the restoration, and oyster populations at the restored reef showed annual increases across all five years of post-restoration monitoring, which showed that oysters were surviving and populations were increasing over time. Unrestored oyster reefs either remained at similar oyster densities, or their populations declined over this same time period, depending on the distance from shore for the reef. Oyster sizes were were similar between restored and unrestored sites within three years of the restoration, and in the area of the restored reef that was open to commercial oyster harvest (about 40% of the reef), local oystermen reported finding legal size oysters on and near the reef beginning in 2022.

“The Lone Cabbage Project is the most successful oyster restoration project in Florida to date, and this success is really driven by a few key attributes” described project co-PI Bill Pine “First, we learned from our pilot project that the recovery of Lone Cabbage Reef was limited by the available substrate, and not oyster spat. This meant if we could provide a suitable substrate, then the naturally available oyster spat would be able to settle and grow on the substrate. Another key point is that we mimicked what we observed naturally occurring in the system. For example, we used locally sourced material that is the same type of limestone as found in nearby areas such as Waccasassa Bay and Ozello that we knew could support oyster spat and adult oysters. We also built the reef to the same elevation as healthy natural reefs in Suwannee Sound using rocks of multiple sizes which created a lot of gaps and places for spat to settle and grow. Our partnerships with oyster harvesters in the area were critical to learning more about the oyster reefs in the region and how they had changed over time. This was key to informing the design of the Lone Cabbage Restoration.”

Even though the restoration of Lone Cabbage was a success, this restoration replaces only about 3-4% of the oyster reef area that has been lost in the Big Bend region. What does this mean for oysters along the Nature Coast? Dr. Pine shared his thoughts “The restoration of Lone Cabbage shows that large restoration projects can be done successfully. And now that we have learned how to do these projects, my hope is our local community partners can lead oyster restoration efforts in the region. The people that live and work in this area are the ones whose livelihoods and lifestyles depend on healthy ecosystems, and they can use the lessons learned from Lone Cabbage to lead other projects. At the same time, research partnerships should work to understand why oyster populations have collapsed and require restoration in the first place. This region of Florida is often considered “pristine” but we have documented widespread declines in oyster populations since the 1980s and we really don’t understand what is driving those declines.”

Here are some other key take away points from this project:

Short Term Economic Impacts – The construction phase of the Lone Cabbage Reef restoration had local economic benefits. We estimate that the implementation phase of the project supported 44 full–time and part-time jobs earning $1.01 million in labor income and generated $5.08 million in total industry output, including $3.02 million in total value added within the regional economy.

Skill training – Oyster harvesters worked on this project providing technical skill in the construction, oyster monitoring, and servicing of the water quality monitoring stations. Involving local oyster harvesters in all aspects of the project created opportunities for the university researchers to learn from the harvesters, and the harvesters to learn from the researchers.

Water quality – Salinity was measured every hour at six different locations for more than five years to examine how the restoration of Lone Cabbage Reef may have changed salinity patterns in Suwannee Sound. These data do not suggest the restoration of the Lone Cabbage Reef had any change on salinity in Suwannee Sound.

What’s next – This project is an example of translating research to on-the-ground conservation actions that can provide meaningful benefit to ecosystems and their human users. In the short-term, community-led restoration efforts can reverse observed oyster reef losses. These community efforts can provide employment opportunities for under-employed community members. Long-term the drivers of large-scale oyster reef loss in this region must be identified, and efforts to reverse these losses undertaken at a meaningful scale to recover the ecosystem and fishery benefits provided by oyster reefs in the Big Bend region of Florida.

To find out more about this project, view the online portal. Access the publications below.

Seavey, J.R., Pine III, W.E., Frederick, P., Sturmer, L. and Berrigan, M., 2011. Decadal changes in oyster reefs in the Big Bend of Florida’s Gulf Coast. Ecosphere, 2(10), pp.1-14.

Pine III, W.E., Johnson, F.A., Frederick, P.C. and Coggins, L.G., 2022. Adaptive management in practice and the problem of application at multiple scales—insights from oyster reef restoration on Florida’s Gulf coast. Marine and Coastal Fisheries, 14(1), p.e10192.

Pine III, W.E., Brucker, J., Davis, M., Geiger, S., Gandy, R., Shantz, A., Stewart Merrill, T. and Camp, E.V., 2023. Collapsed oyster populations in large Florida estuaries appear resistant to restoration using traditional cultching methods—Insights from ongoing efforts in multiple systems. Marine and Coastal Fisheries, 15(5), p.e10249.

Aufmuth, J. J. Moore, W. Pine III, B. Ennis. In-review. An oyster’s pearl: restoring the elevation of Lone Cabbage Reef, Florida. Restoration Ecology

Moore, J.F. and Pine III, W.E., 2021. Bootstrap methods can help evaluate monitoring program performance to inform restoration as part of an adaptive management program. PeerJ, 9, p.e11378.

Moore, J.F., Pine III, W.E., Frederick, P.C., Beck, S., Moreno, M., Dodrill, M.J., Boone, M., Sturmer, L. and Yurek, S., 2020. Trends in oyster populations in the Northeastern Gulf of Mexico: an assessment of river discharge and fishing effects over time and space. Marine and Coastal Fisheries, 12(3), pp.191-204.

Pine, W. E. III, J. A. Moore, J. Aufmuth, M. Moreno, T. Coleman, J. Casteel, S. Beck, B. Ennis, and P. Frederick. In-review. Restoration is a partial, but not complete solution for long-term declines in oyster populations—a case history from the northeastern Gulf of Mexico. Marine and Coastal Fisheries.